- Home

- Franklin W. Dixon

Operation: Survival Page 2

Operation: Survival Read online

Page 2

“I’m seeing a pattern here. Not a happy pattern,” Joe commented.

“Yeah, I don’t think ATAC is sending us on a fun-filled vacation after all,” I said.

I continued reading. “‘I’m not surprised another kid ended up dead under Linc’s supervision,’ a worker from the Montana camp, who would only speak anonymously, commented. ‘Linc would rather kill a kid than damage his success rate. The white-water accident that closed down Camp Character was no accident. Linc’s methods weren’t working on the kid, so the kid ended up dead. You don’t screw up the statistics when you’re dead.’”

The picture of the kids around the campfire returned. It was hard to look at Zack’s grinning face, now that I knew what had happened to him. Now that I knew he hadn’t made it out of the camp alive.

“Your mission is to go undercover at Camp Wilderness.” The voice coming out of the game player was clearly electronically generated. There was no way to identify the speaker, but we knew it was Q.T.

“You must determine if Zack Maguire’s death was accidental. Or if he was murdered.”

3 COVER STORIES

“We need you to sign permission slips for a science trip,” I said that night at dinner.

My parents, Frank, and Aunt Trudy all stared at me. Probably because what they heard was more like “Wah neeg oo oo gine ermissgin ips or ience rip.”

Or maybe because they were all horrified by the sight of me talking with my mouth way too full.

I couldn’t help it. When Aunt Trudy serves up her chocolate chip cookie pie, my mouth is going to be full. It’s a cookie. And a pie. That should explain everything. Unless your taste buds have been surgically removed.

I chugged down some moo juice—as I used to call milk when I was four—and tried again. “Permission slips. We need you to sign them. The top kids in all the science classes get to spend a week at Moosetail Lake.”

“Moosehead,” Frank corrected.

Tail. Head. What was the big deal? They were both attached to the moose. I don’t know why Frank has to be so technical about stuff.

“It’s in Maine,” I said. “We’re going to study the ecosystem of the lake.”

Did you like how I tossed in the word ecosystem? I did that for Mom. She’s really into recycling and saving the planet and everything. I figured if she was leaning toward saying no, using the E word might push her toward yes.

“Studying the ecosystem.” Mom shot a smile at me. “While canoeing, and rafting, and—”

I held up both hands. “Okay, you got me.” Like always, I thought. Sometimes when I’m around Mom, I feel like my skull is made of cling wrap. Every thought visible.

“There will be some fun to be had,” I confessed. “But I’m sure we’ll learn something, too. So, will you sign?” I slid the phony permission slips across the table.

We got the slips in our ATAC pizza package—along with two plane tickets to Maine, details about our false identities, and bios of Zack Maguire and Linc Saunders.

Mom and Dad exchanged a glance. You know, one of those glances that are like entire conversations. “I guess we can survive without you two for a week.” Mom pulled a pen from behind her ear. She always has a pen stuck back there. I think it’s a research librarian thing. She signed and gave me back the slips.

Aunt Trudy took the pen from Mom and started jotting down a list on the back of a grocery receipt she found in her pocket. “Underwear—ten pairs each. Sods—twelve pairs each. Sweaters, wool—,” she mumbled.

“Aunt T, we’re only going for a week,” I reminded her.

“And you’re telling me in that week one of you isn’t going to fall into the lake at least once and need a complete change of clothing?” Aunt Trudy continued writing.

Aunt T thinks Frank and I are about five. I mean, come on, who falls into a lake? I haven’t fallen into a body of water since I was … okay, since I was thirteen. But usually I have no problem surviving on one pair of underwear a day.

Honestly, I can survive on less. I don’t really understand the need for new underwear every single day. Every couple works for me.

Mom had more important things on her mind than wet boxers. “At this time of year, you may run into some black bears up there,” she told me and Frank. “If you see one, do what the Native Americans used to.”

She lifted her arms into the air. Still holding her fork. She didn’t realize she was in danger of ending up with some meatloaf on her head.

“Hold your hands over your head and say, ‘Hello, Brother Bear. I did not mean to disturb you. I will leave your territory and leave you in peace,’” Mom instructed.

“What about that bear spray? One of the jumbo cans. I’m thinkin’ that might be a better way to deal with Brother Bear,” I said.

They really do make the stuff. I thought it was a joke the first time I saw an ad for it in a camping magazine. Because once you’re close enough to a bear to zap it with spray, you’re already a lot closer than I want to be. But I have to say, the spray seemed a lot safer to me than Mom’s method.

“The spray might just make them angry,” Dad jumped in. “And an angry bear is nothing you want to deal with.”

“A lot of bears attack simply because they’re surprised,” Mom explained. “That’s why talking to them is good. You don’t have to use the exact words I gave you—say anything. You can even sing if you want to—”

“Mom, what are you saying? We’ve all heard Frank sing in the shower. It’s enough to make a baby kitten go on a killing spree.”

Mom shook her head at me. But she smiled, too. So the head shake didn’t really count. “Just make noise and keep your hands over your head. That makes you look bigger.”

“If they do attack, you’re supposed to play dead, right?” Frank asked.

“Good thing I just helped a kid do research on bears. I know all the answers,” Mom replied. “You should play dead—even if the bear bites you. Except with black bears. Black bears are scavengers, not hunters. So if one bites, it’s probably decided you’re food. That means you have to go on the attack.”

I nodded. Good to know. But I had the feeling Frank and I should be a lot more worried about Linc Saunders—a potential murderer—than bears.

Frank reached for the last piece of cookie pie. But I got there first. “I’m gonna take this upstairs. I need to get some homework in,” I announced.

“Me too,” Frank said. I led the way up to my room.

“Wimps, wimps, wimps,” Playback called.

“It’s not nice to talk to Frank that way,” I told our parrot.

Playback ruffled his feathers. Frank ignored me. He does that a lot. He flopped down on my bed. I pulled the files we’d received from ATAC out of the top drawer of my desk.

There was a file for Brian Moya. And a file for Steve Neemy. Neemy’s stats included dark brown hair and brown eyes, so I handed that file over to Frank.

I flipped open the file for Brian Moya. The blond hair, blue eyes description matched me. “Brian Moya, Brian Moya, Brian Moya,” I said aloud. I wanted to get a feel for the name.

“You sound like Playback,” Frank commented.

This time I ignored him. “Brian Moya,” I said one more time. Then I started to read the police report for Brian. Make that me. “Wow. I was arrested for shoplifting three times,” I told Frank. “The last time, the judge ordered me to a stay at Camp Wilderness.”

“I trashed a convenience store in an act of gang violence,” Frank answered.

I tried to imagine Frank trashing anything. It made my head hurt. He doesn’t even trash his bedroom. He’s freakishly neat. I’ve been thinking about having him studied by a team of scientists. I suspect he isn’t a hundred percent human.

“Okay, so we should flesh out our cover stories.” Frank stared up at the ceiling. “Steve Neemy is from Brooklyn. So what gang should I have been in?”

I sat down in front of my computer and Googled “Brooklyn” and “gang.” A lot of Mafia stuff came up.

Not what I was looking for.

I tried “teen gang.” Yeah, this is more what we needed. “There’s some stuff on big gangs, like the Vice Lords and the Gangster Disciples. But if a guy from one of those gangs is at the camp—”

“It would be way too easy for them to figure out I’m a fake,” Frank finished for me. We do that sometimes. Complete each other’s thoughts.

“Right. Even if you studied from now until we leave, you’d never be able to get down all the details,” I agreed. Which is saying something. Because Frank’s a study champion.

“So Steve Neemy—”

“You mean you,” I interrupted.

“Right. So I’m not from a major league gang. I’m from a smaller league gang,” Frank said. “Just me and some guys from the neighborhood. And I’m not one of the leaders or anything. I’m—”

A knock cut Frank off “Enter!” I called.

Dad came inside and closed the door behind him. “Your mother is doing a bear-by-bear survival breakdown for you two. I think I convinced her she didn’t have to include polar bears. You know your mom. Thorough. Plus, she worries.”

Like Dad doesn’t. He worries a lot more than Mom does. But maybe that’s because he knows we’re ATAC. That gives him extra stuff to be worried about.

“You all ready for the trip?” Dad asked.

Let me translate the fatherspeak: Are you sure you don’t need my expert advice? Since I am an only partly retired PI, and I was a cop for a million years, and, oh, yeah, I founded ATAC?

Frank and I keep waiting for Dad to realize we can handle ourselves. We’ve completed tons of missions.

“Yep. We’re just doing a little prep on our cover stories,” Frank said.

Dad leaned against the doorframe. Like he was just casually hanging out. But I could see how tight the muscles in his neck were. “Uh-huh. And that’s going okay?” he asked.

Translation: I have years, and years, and yes, years more experience than you boys. I think it would be smart of you to ask for a little advice.

“Going great,” I answered. I did that thing where you mean to nod once, but then end up looking like one of those bobblehead dolls. I hoped all those extra head bobs would convince Dad that I really meant everything was going great. That he didn’t really have to worry, because Frank and I were on top of things.

Then there was one of those silences. You know the kind. A silence that is basically a battle of wills. Who will speak first? Who’s gonna crack?

Frank didn’t talk. I didn’t talk. Dad didn’t talk. Even Playback didn’t talk—for once.

I wanted to throw Dad a bone. I did. Just give him my opinion on the Linc Saunders is-he-a-murderer-or-not question. Or ask him his opinion.

But the thing is, parents are hard to train. If Frank and I let Dad talk the case over with us this time, he’d want to do it every time.

And Dad always has these retro ideas about everything. For example, he doesn’t see why we need our ultimate, extreme motorcycles. I mean, he makes sure we’ve got everything we need—he totally souped them up a short while ago—but he’d rather have us ride Vespas or something. Again, because he worries.

And probably because he didn’t get to ride an awesome motorcycle back in the day, so he doesn’t see any reason we should now.

“Well, if you need me, you know where I’ll be,” Dad finally said.

Hey, we won. But we don’t always. Dad is truly superior at the silence game.

Words came pouring out of me the second the door closed behind him. “So you’re going to be from a farm team kinda gang. Nothing that anybody but you and your crime-lovin’ buds know about. Do you have a name? The Pythons? The Vicious Sisters? The Polar Bears?”

“Let’s get back to that,” Frank said. “I thought of something while—” He hesitated.

“While we were waiting for Dad to realize we’re big boys who can handle our missions on our own?” I asked.

“Yeah. Anyway, I think that one of us should pretend to be unathletic,” Frank went on. “I have the feeling that Saunders won’t have any patience for a guy who can’t meet all those physical challenges he lines up.”

“I can see that. That quote from him made it sound like he didn’t have a lot of respect for kids who weren’t able to find their core of heavy metal.”

“Steel,” Frank corrected me.

Will he ever get my sense of humor?

“And Zack’s mother said Zack didn’t have any experience camping or anything like that,” I added. “Maybe he kept messing up. Maybe Zack wasn’t strong enough to be the kind of Camp Wilderness success story Saunders loves.”

“Maybe,” Frank agreed. “I think it would be interesting to see how Saunders treats someone who isn’t in great shape.”

“Well, you’re going to have to be that someone. I’m a genius at the undercover stuff But no one’s going to believe I’m a couch potato.” I flexed for Frank. “Maybe I should be a guy with attitude. A guy who isn’t going to become a rehabilitation poster child for Saunders, no matter what. I think that would bug him as much as an out-of-shape kid.”

“One of us should definitely give Saunders some attitude,” Frank said. “That’s a great idea.”

“So you be the wimp, wimp, wimp. And I’ll be the outlaw who won’t be brought down by a stay at Saunders’s pathetic little camp.”

Frank pulled a quarter out of his pocket. “I’ll flip you for it.”

“Do you really think you can pull off an extreme bad-boy attitude? You’re not exactly … Let’s face it, Frank. You’re a teacher’s pet kinda guy. Every adult you’ve ever met loves you.”

Frank gave me the Look of Doom. “Heads,” I said.

The quarter went up. And came back down—tail up.

“And you lose. Shall I call you Mr. Potato, or do you prefer Spuddy?” Frank asked.

I shrugged. “At least I’ll be able to check out Chet’s theory.”

“What?”

“So I have to pretend to be out of shape and everything. But I’m still Brian Moya, shoplifter. And that means I’m still a Bad Boy. With capital Bs. If Chet’s right, the girls at the camp should think I’m The Man.”

4 WELCOME TO CAMP WILDERNESS

I was sitting in the back of a police cruiser. Me. Frank Hardy. Son of Fenton Hardy, a former cop. It was just so wrong. In so many ways.

Wait. No. It’s not me, Frank Hardy, getting a police escort from the airport to Camp Wilderness, I reminded myself. It’s Steve Neemy.

But the weird thing was—I still felt kind of ashamed. I felt like everyone in the little town of Greenville was looking at me. Wondering what Frank Hardy had done to get himself sent to reform camp.

I told myself to start thinking like Steve. Steve was supposed to be a hard case. A guy with attitude. A guy who had no use for Linc Saunders and his rehabilitation program.

I met the gaze of the middle-aged man who was using the crosswalk while the cruiser was stopped at a red light.

What are you looking at? I tried to ask him with my eyes. What have you done with your life that’s so special? What gives you the right to feel superior to me?

The man looked away first. Good. I’d channeled Steve pretty well.

The cruiser exited the main street of the town. It was only a couple of blocks long. A little grocery. A bakery. A bait shop where you could get a hunting and fishing license. That kind of thing.

The houses started coming farther and farther apart. Then we turned onto a dirt road. About five miles down it, I saw the sign. The sign that we’d seen in our mission assignment: WELCOME TO CAMP WILDERNESS.

Looking at it made all the little hairs on my arms and the back of my neck stand on end.

“This is it, huh?” Joe said.

The cop behind the wheel glanced over his shoulder. “This is it,” he answered. “Last chance. You screw up here, and it’s straight to juvie. Do not pass Go. Do not collect two hundred dollars.”

He didn’t say it in a nasty kind

of way. More in an FYI kind of way. Or even an I-don’t-want-to-see-you-mess-your-life-up way.

“Unless you happen to turn eighteen while you’re at the camp,” his partner added. He gave us a not-all-that-friendly smile, and I noticed he had a gap between his front teeth. “Then you go straight to big-boy prison if you don’t keep your nose clean here.”

We pulled up in front of a small, plain building made of pine planks. A couple of jeeps were parked in front of it. A quarter mile or so behind it was a long row of bunks.

“Somehow I don’t think we’re going to be getting little mints on our pillows,” Joe said.

I ignored him. But not in the way I usually do. I did it in a Steve Neemy why-are-you-even-talking-to-me way.

The cops opened the back doors for me and Joe. We couldn’t open them ourselves. The backseats of cop cars don’t have door handles on the inside. Which is logical. Can’t give the criminal types an easy escape route.

Then the cops marched us into what turned out to be Linc Saunders’s place. An office, bedroom, kitchenette combo. “Neemy and Moya for you,” the gap-toothed cop announced.

Saunders nodded and the cops left. “Have a seat, boys. I was just about to run through the Camp Wilderness philosophy for Miss Hanks here. She’s a new arrival as well.”

The teenage girl sitting on the sofa in front of Saunders’s desk didn’t look over at me and Joe. She kept her eyes on the bearskin rug on the floor. I tried to keep my eyes off it.

See, my grandmother used to have this fox scarf kind of thing. It had its head still attached—just like the bear rug did. When I was little I used to dream that the fox came alive and tried to claw my face—

You know what? This is not information you need to know. Back to the story.

I sat down on one side of the girl. Joe planted himself on the other.

The girl was cute, I’ll admit it. I wondered if Joe was thinking about Chet’s bad-boy theory.

Saunders leaned back in his leather chair. The front legs came off the ground. The back legs creaked under his weight. It’s not that he was fat. He had less body fat than anybody I’d ever seen.

The Great Pumpkin Smash

The Great Pumpkin Smash Who Let the Frogs Out?

Who Let the Frogs Out? Return to Black Bear Mountain

Return to Black Bear Mountain A Treacherous Tide

A Treacherous Tide Bug-Napped

Bug-Napped The Disappearance

The Disappearance Sea Life Secrets

Sea Life Secrets The Mystery of the Chinese Junk

The Mystery of the Chinese Junk A Skateboard Cat-astrophe

A Skateboard Cat-astrophe Too Many Traitors

Too Many Traitors Galaxy X

Galaxy X The Secret Panel

The Secret Panel The Secret of Wildcat Swamp

The Secret of Wildcat Swamp The Secret of the Caves

The Secret of the Caves The Caribbean Cruise Caper

The Caribbean Cruise Caper Without a Trace

Without a Trace The Mystery of the Spiral Bridge

The Mystery of the Spiral Bridge Movie Menace

Movie Menace Dungeons & Detectives

Dungeons & Detectives Water-Ski Wipeout

Water-Ski Wipeout The Case of the Psychic's Vision

The Case of the Psychic's Vision X-plosion

X-plosion Deathgame

Deathgame The Apeman's Secret

The Apeman's Secret A Will to Survive

A Will to Survive Mystery at Devil's Paw

Mystery at Devil's Paw Blood Money

Blood Money The Mark on the Door

The Mark on the Door Scene of the Crime

Scene of the Crime The Gray Hunter's Revenge

The Gray Hunter's Revenge Stolen Identity

Stolen Identity The Mummy's Curse

The Mummy's Curse Mystery of Smugglers Cove

Mystery of Smugglers Cove Diplomatic Deceit

Diplomatic Deceit The Haunted Fort

The Haunted Fort The Crisscross Shadow

The Crisscross Shadow Secret of the Red Arrow

Secret of the Red Arrow Trial and Terror

Trial and Terror The Short-Wave Mystery

The Short-Wave Mystery The Spy That Never Lies

The Spy That Never Lies Operation: Survival

Operation: Survival Deception on the Set

Deception on the Set The Sign of the Crooked Arrow

The Sign of the Crooked Arrow Hunting for Hidden Gold

Hunting for Hidden Gold Disaster for Hire

Disaster for Hire The Clue in the Embers

The Clue in the Embers Danger Zone

Danger Zone The Hidden Harbor Mystery

The Hidden Harbor Mystery Eye on Crime

Eye on Crime A Game Called Chaos

A Game Called Chaos The Bicycle Thief

The Bicycle Thief The Missing Playbook

The Missing Playbook Survival Run

Survival Run The Bombay Boomerang

The Bombay Boomerang Mystery of the Samurai Sword

Mystery of the Samurai Sword Burned

Burned Death and Diamonds

Death and Diamonds Murder at the Mall

Murder at the Mall The Prime-Time Crime

The Prime-Time Crime Hide-and-Sneak

Hide-and-Sneak Training for Trouble

Training for Trouble Trouble in Paradise

Trouble in Paradise While the Clock Ticked

While the Clock Ticked The Alaskan Adventure

The Alaskan Adventure The Lost Brother

The Lost Brother Tunnel of Secrets

Tunnel of Secrets A Killing in the Market

A Killing in the Market The Curse of the Ancient Emerald

The Curse of the Ancient Emerald The Arctic Patrol Mystery

The Arctic Patrol Mystery Past and Present Danger

Past and Present Danger The Castle Conundrum (Hardy Boys)

The Castle Conundrum (Hardy Boys) Farming Fear

Farming Fear Nowhere to Run

Nowhere to Run The Secret of the Soldier's Gold

The Secret of the Soldier's Gold Danger on Vampire Trail

Danger on Vampire Trail The Lure of the Italian Treasure

The Lure of the Italian Treasure The Mystery of Cabin Island

The Mystery of Cabin Island Darkness Falls

Darkness Falls Night of the Werewolf

Night of the Werewolf Danger in the Extreme

Danger in the Extreme The Lazarus Plot

The Lazarus Plot The Hooded Hawk Mystery

The Hooded Hawk Mystery Double Trouble

Double Trouble Forever Lost

Forever Lost Pushed

Pushed The Great Airport Mystery

The Great Airport Mystery The Hunt for Four Brothers

The Hunt for Four Brothers The Disappearing Floor

The Disappearing Floor Motocross Madness

Motocross Madness Foul Play

Foul Play High-Speed Showdown

High-Speed Showdown The Mummy Case

The Mummy Case The Firebird Rocket

The Firebird Rocket Trouble in Warp Space

Trouble in Warp Space Ship of Secrets

Ship of Secrets Line of Fire

Line of Fire The Clue of the Broken Blade

The Clue of the Broken Blade Medieval Upheaval

Medieval Upheaval Witness to Murder

Witness to Murder The Giant Rat of Sumatra

The Giant Rat of Sumatra Attack of the Bayport Beast

Attack of the Bayport Beast The Borgia Dagger

The Borgia Dagger Scavenger Hunt Heist

Scavenger Hunt Heist No Way Out

No Way Out Murder House

Murder House The X-Factor

The X-Factor The Desert Thieves

The Desert Thieves Mystery of the Phantom Heist

Mystery of the Phantom Heist The Battle of Bayport

The Battle of Bayport Final Cut

Final Cut Brother Against Brother

Brother Against Brother Private Killer

Private Killer The Mystery of the Black Rhino

The Mystery of the Black Rhino Feeding Frenzy

Feeding Frenzy Castle Fear

Castle Fear A Figure in Hiding

A Figure in Hiding Hopping Mad

Hopping Mad Dead on Target

Dead on Target Skin and Bones

Skin and Bones The Secret Warning

The Secret Warning Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood The Shattered Helmet

The Shattered Helmet Boardwalk Bust

Boardwalk Bust Terror at High Tide

Terror at High Tide In Plane Sight

In Plane Sight The London Deception

The London Deception Evil, Inc.

Evil, Inc. Deprivation House

Deprivation House The Mystery of the Aztec Warrior

The Mystery of the Aztec Warrior First Day, Worst Day

First Day, Worst Day Bonfire Masquerade

Bonfire Masquerade Killer Connections

Killer Connections Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Warehouse Rumble

Warehouse Rumble The Chase for the Mystery Twister

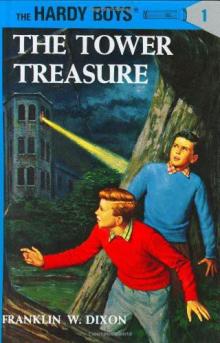

The Chase for the Mystery Twister The Tower Treasure thb-1

The Tower Treasure thb-1 The Children of the Lost

The Children of the Lost The Last Laugh

The Last Laugh Trick-or-Trouble

Trick-or-Trouble Perfect Getaway

Perfect Getaway Nightmare in Angel City

Nightmare in Angel City Edge of Destruction

Edge of Destruction Fright Wave

Fright Wave The Jungle Pyramid

The Jungle Pyramid Footprints Under the Window

Footprints Under the Window The Gross Ghost Mystery

The Gross Ghost Mystery A Monster of a Mystery

A Monster of a Mystery House Arrest

House Arrest Mystery of the Desert Giant

Mystery of the Desert Giant Talent Show Tricks

Talent Show Tricks The Sting of the Scorpion

The Sting of the Scorpion The Secret of Skull Mountain

The Secret of Skull Mountain The Missing Chums

The Missing Chums Kickoff to Danger

Kickoff to Danger Cult of Crime

Cult of Crime Running on Fumes

Running on Fumes Martial Law

Martial Law The Pentagon Spy

The Pentagon Spy Hazed

Hazed The Secret Agent on Flight 101

The Secret Agent on Flight 101 Running on Empty

Running on Empty Top Ten Ways to Die

Top Ten Ways to Die The Missing Mitt

The Missing Mitt The Melted Coins

The Melted Coins The Rocky Road to Revenge

The Rocky Road to Revenge The Masked Monkey

The Masked Monkey Lost in Gator Swamp

Lost in Gator Swamp Extreme Danger

Extreme Danger Street Spies

Street Spies The Wailing Siren Mystery

The Wailing Siren Mystery The Dangerous Transmission

The Dangerous Transmission Hurricane Joe

Hurricane Joe The Crisscross Crime

The Crisscross Crime Mystery of the Whale Tattoo

Mystery of the Whale Tattoo The House on the Cliff

The House on the Cliff Camping Chaos

Camping Chaos Ghost of a Chance

Ghost of a Chance Tagged for Terror

Tagged for Terror Thrill Ride

Thrill Ride Fossil Frenzy

Fossil Frenzy The Time Warp Wonder

The Time Warp Wonder Ghost Stories

Ghost Stories Speed Times Five

Speed Times Five What Happened at Midnight

What Happened at Midnight Three-Ring Terror

Three-Ring Terror Trouble at the Arcade

Trouble at the Arcade The Clue of the Hissing Serpent

The Clue of the Hissing Serpent Trouble in the Pipeline

Trouble in the Pipeline The Tower Treasure

The Tower Treasure Hostages of Hate

Hostages of Hate The Crowning Terror

The Crowning Terror Daredevils

Daredevils The Vanishing Thieves

The Vanishing Thieves Killer Mission

Killer Mission The Mark of the Blue Tattoo

The Mark of the Blue Tattoo The Witchmaster's Key

The Witchmaster's Key The Deadliest Dare

The Deadliest Dare Peril at Granite Peak

Peril at Granite Peak The Secret Of The Old Mill thb-3

The Secret Of The Old Mill thb-3 Rocky Road

Rocky Road The Demolition Mission

The Demolition Mission Blown Away

Blown Away Passport to Danger

Passport to Danger The Shore Road Mystery

The Shore Road Mystery Trouble Times Two

Trouble Times Two The Yellow Feather Mystery

The Yellow Feather Mystery One False Step

One False Step Crime in the Cards

Crime in the Cards Thick as Thieves

Thick as Thieves The Clue of the Screeching Owl

The Clue of the Screeching Owl The Pacific Conspiracy

The Pacific Conspiracy The Genius Thieves

The Genius Thieves The Flickering Torch Mystery

The Flickering Torch Mystery Into Thin Air

Into Thin Air Highway Robbery

Highway Robbery Deadfall

Deadfall Mystery of the Flying Express

Mystery of the Flying Express The Viking Symbol Mystery

The Viking Symbol Mystery The End of the Trail

The End of the Trail The Number File

The Number File Gold Medal Murder

Gold Medal Murder Bound for Danger

Bound for Danger Collision Course

Collision Course The Madman of Black Bear Mountain

The Madman of Black Bear Mountain The Secret of the Lost Tunnel

The Secret of the Lost Tunnel The Stone Idol

The Stone Idol The Secret of Pirates' Hill

The Secret of Pirates' Hill A Con Artist in Paris

A Con Artist in Paris The Mysterious Caravan

The Mysterious Caravan The Secret of Sigma Seven

The Secret of Sigma Seven The Twisted Claw

The Twisted Claw The Phantom Freighter

The Phantom Freighter The Dead Season

The Dead Season The Video Game Bandit

The Video Game Bandit The Vanishing Game

The Vanishing Game Typhoon Island

Typhoon Island